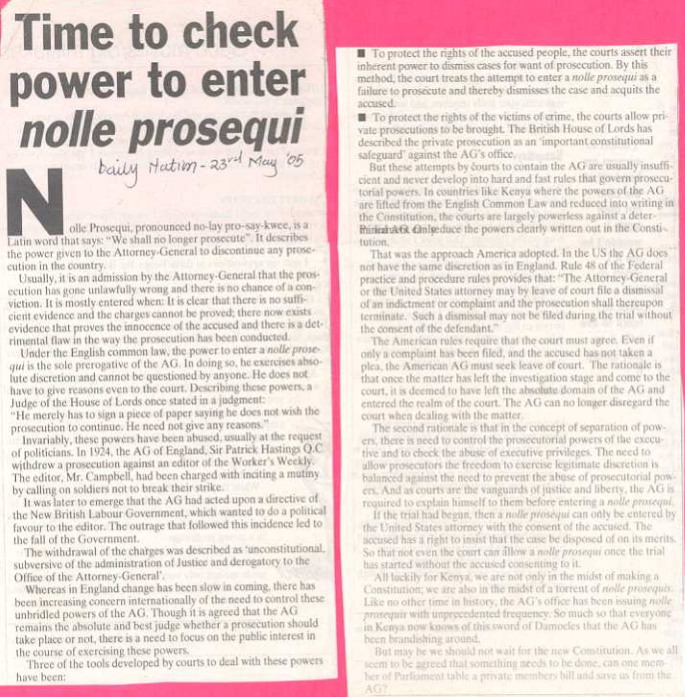

Nolle prosequi, pronounced no-lay pro-say-kwee, is a Latin word that says: “We shall no longer prosecute.” It describes the power given to the AG to discontinue any prosecution in the country. Usually, it is an admission by the AG that the prosecution has gone unlawfully wrong and there is no chance of a conviction. It is mostly entered when: it is clear that there is no sufficient evidence and the charged cannot be proved; there are now exists evidence that proves the innocence of the accused and there is a detrimental flaw in the way the prosecution has been conducted.

Under the English common law, the power to enter a Nolle prosequi, is the sole prerogative of the AG. In doing so, he exercises absolute discretion and cannot be questioned by anyone. He does not have to give reasons even to the court, describing these powers, a judge of the House of Lords once stated in a judgment: “he merely has to sign a piece of paper saying he does not wish the prosecution to continue. He need not give any reasons.”

Invariably, these powers have been abused, usually at the request of politicians. In 1924, the AG of England, Sir Patrick Hastings, Q.C. withdrew a prosecution against an editor of the Workers’ Weekly. The editor, Mr. Campbell, had been charged with inciting a mutiny by calling on soldiers not to break their strike. It was later to emerge that the AG had acted upon the directive of the New British Labor Government which wanted to do a political favor to the editor. The outrage that followed this incident led to the fall of the government. The withdrawal was described as,” unconstitutional, subversive of the administration of justice and deregulatory to the office of the AG.”

Where as in England change has been slow in coming, there has been increasing concern internationally of the need to control these unbridled powers of the AG. Though it is agreed that the AG remains the absolute and best judge whether a prosecution should take place or not, there is need to focus on the public interest on the course of exercising these powers. Three of the tools developed by courts to deal with these powers have been:

- To protect the rights of the accused people, the courts assert their inherent powers to dismiss cases for want of prosecution. Bu this method, the court treats the attempt to enter a Nolle prosequi, as a failure to prosecute and thereby dismisses the case and acquits the accused.

- To protect the rights of the victims of crime, the court allows private prosecutions to be brought. The British House of Lords has described the private prosecution as an important constitutional safeguard against AG’s office.

But these attempts by courts to contain the AG are usually insufficient and never develop into hard and fast rules that govern prosecutor powers. In countries like Kenya where the powers of the AG are lifted from the English Common Law and reduced into writing in the Constitution, the courts are largely powerless against a determined AG to reduce the powers clearly written out in the constitution. That was the approach America adopted. In the USA the AG does not have the same discretion as in England. Rule 48 of the federal practice and procedure rules provides that: “The Attorney General or the US Attorney may, by leave of court, file a dismissal of an indictment or complaint that the prosecution shall thereupon terminate. Such a dismissal may not be filed during the trial without the consent of the defendant”.

The American rules require that the courts must agree, even if only a complaint has been filed, and the accused has not taken a plea, the American AG must seek leave of court. The rationale is that once the matter has left the investigation stage and come to the court, it is deemed to have left the absolute domain of the AG and entered the realm of the court. The AG can no longer disregard the court when dealing with the matter. The second rationale is that in the concept of separation of powers, there is no need to control the prosecutorial powers of the executive and check the abuse of executive privileges. The need to allow prosecutors the freedom to exercise legitimate discretion is balanced against the need to prevent the abuse of prosecutorial powers. And as courts are the vanguard of justice and liberty, the AG is required to explain himself to them before entering a Nolle prosequi. If the trial had begun, then a Nolle prosequi, can only be entered by the United States attorney with the consent of the accuser. The accused has a right to insist that the case be dismissed on its merit so that not even the court can allow a Nolle prosequi once the trial has started without the accused consenting to it.

All luckily for Kenya, we are not only in the midst of making a Constitution; we are also in the midst of a torrent of Nolle prosequi. Like no other time in history, the AG’s office has been issuing Nolle prosequi with unprecedented frequency. So much so that everyone in Kenya now knows of this sword of Damocles that the AG has been brandishing around.

But maybe we should not wait for the new Constitution. As we all seem to be agreed that something needs to be done, can one Member of Parliament table a private members bill and save us from the AG.